With a Rifle in My Hand

and Eretz Yisrael in My Heart

by Dov Levin, Jerusalem

Translated by Shalom Bronstein

Chapters of Reminiscence: Kovno (Kaunas); The Partisans' Forests; Illegal Immigration to Eretz Yisrael

l[The events related in this account are far from describing all that happened to me in my first 20 years, but I have attempted to re-enter the shoes of those years.]

I. Before the Nazi Conquest

My twin sister Batya (Bassia) and I were born on 27 January 1925 in the city of Kovno – the capital of independent Lithuania between the two world wars. My father, Zvi-Hirsch Levin and my mother, Bluma nee Wigoder, maintained a traditional religious Jewish home that was infused with the Zionist spirit. They made every attempt to provide us with a national Jewish education beginning with nursery school and eventually the Shwabbe's Hebrew gymnasium [high school]. From the age of twelve, I was a member of Hashomer Hatzair, the socialist Zionist youth movement. The activities and very being of the movement were Hebrew oriented with the goal being Aliya to Eretz Yisrael in fulfillment of the words of the song, “To work, to train as pioneers, to the kibbutz, to defend.” Our attraction to socialism and the Soviet Union were expressed on the romantic level expressed in the words of the song 'Tulips' – “You will be a red commissar and I will be a compassionate nurse …”

The author and his twin sister, Bassia, age 5 (1930)

The author's parents: Bluma nee' Wigoder and Tzvi Hirsh Levin in 1923.

The author (eighth from the right, top row) among 4th grade students in Shwabbe's Gymnasium

On September 1, 1939 when World War II broke out, our literature and Jewish history teacher, Meir Kantorovitz, devoted his lesson to preparing us for the anticipated dangers that awaited us as the war proceeded and called on us to always remember to act as proud Jews. Indeed, I always remembered his directive to us.

In my family, it was understood that after I completed my high school studies in Kovno, I would go on Aliya to Eretz Yisrael in order to study engineering at the Technion in Haifa. However, this dream evaporated with the take-over of Lithuania by the Red Army (the Soviets) on 15 June 1940.

Under Soviet Rule

That day, it was a Shabbat; I was participating in the Shomer Hashomer Hatzair summer camp that was held in the village of Klibanishok, near Kovno. Our counselor in this camp was a young woman named Haika Grossman who became well known as the person who was second in command in the Bialystok Ghetto. She arrived in Lithuania at the end of 1939, when it was still an independent country and Zionist activity continued as usual.

" Hashomer Hatzair" youth group members in Kovno with their counselor Haika Grossman (1940).

The author is second from the right, middle row.

When she came to us in Kovno as a war-refugee from the area of Poland taken over by the Soviet Union, she told us that in light of her experience there, that here, too, in Lithuania all Zionist activity would be banned if and when the Soviets would enter. And so, the same thing happened to us. Some of us continued our Zionist activity underground, but most unfortunately studying in Hebrew was forbidden and so we found ourselves in the Sholom Aleichem (spelled in the communist fashion, a phonetic mish mash that bent over backwards to avoid the correct Hebrew spelling). There classes took place in Yiddish, which was an acceptable language according to the Soviet communist regime and was exploited as a propaganda tool among the Jews. The Hebrew language was identified by the new government with Zionism, which was considered anathema to the communist ideology. I knew all of this too well, but it was still difficult for me to reconcile myself to the fact that I would be continuing my studies in a different language in the very same building that for many years housed the legendary Shwabbes Hebrew Gymnasium and where I so enjoyed studying in the Hebrew language which was so dear to me. It is no surprise that at night I would sneak into the storeroom where the Hebrew books were demoted and choose for myself some of the best works of the giants of literature and smuggle them home. In time, I found out that a fair number of the longtime students of the Gymnasium did the same thing and at least one of them was arrested after being betrayed to the authorities by members of the Komsomol [the communist youth organization]. Therefore, we were extremely wary of them!

Three generations of the extended Levin family at a festive gathering in honor of Uncle Benjamin (Hone) Lewin from New York (mid 1930's). The author and his sister are sitting on both ends of the bottom row

This, and even more so - During the year of Soviet rule (June 1940 to June 1941) my family and I, along with many other Jews had additional crises: my parents, like the rest of our neighbors were required from then on to work on the Sabbath as well as on Jewish holidays and so we could no longer continue to properly maintain the tradition of the festive family Sabbath meal accompanied with song. The well known store for tailoring needs and talitot of my grandfather, Reb (Rabbi) Dovid Levin, along with the stores of most of my uncles and relatives were confiscated by the government, and their owners were became unemployed and without the possibility of earning a living. Some of them and many of the Zionist activists were declared 'capitalist exploiters' or simply 'enemies of the Soviet government.' Several, like my teacher Kantorovitz, were even sent into Siberian exile. A similar fate faced me if the Zionist activities that were banned according to the law and that I continued secretly were discovered.

In spite of all of this, among my family and most of the Jews there was the feeling that this situation was better than if God forbid Lithuania would be conquered by the German Nazi army as was anticipated. Thus, the Soviets were the lesser of two evils. On the other hand, the looks of hatred and the threats by our Lithuanian neighbors did not let up since for some reason they blamed us Jews for the Sovietization of their country.

Like other members of our people, I was occasionally assaulted by nightmares concerning the possibility that the Soviets would withdraw from Lithuania. To our misfortune, catastrophe overtook us only a year and a week after Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union.

II. My First Reaction to the Nazi German Conquest

When I came on Sunday morning (22.6.1941) to my high school to receive my graduation certificate, we were surprised by German air force bombing. This was the beginning of the War, known by the code name Operation Barbarossa, between Germany and the Soviet Union. Two days later, when it was clear that the Soviet army was about to retreat in light of the continuing might by the German side, the telephone in our apartment rang. It was my classmate Avraham (Abrasha) Yashpan, who suggested that we flee together deep into Russia in light of the retreating Soviet army. My answer was, “I am staying with my parents and sister!” He said, “You want them to slaughter us?” I then heard the voice of his mother in the background inveigh against him, “Your friend is a more faithful son than you …” I later found out that Abrasha succeeded in escaping and like many of those who fled he joined the Soviet army. He was wounded a few times in battles against the Germans.

My friend Abrashka Yashpan in the Betar Movement uniform

Just a few hours after this conversation when the German army was about to enter the city, the telephone in our apartment in the center of the city at Vilna Street 14 was disconnected. This was true of most of the Jewish homes in Kovno. This was the first anti-Jewish act of the Lithuanian nationalists who meanwhile had taken over the city. In one of the announcements that I heard over the radio by their commander, Colonel Jurgis Bobelis, for every German killed, 100 Jews would be put to death.

Before we even had time to think about these blood-curdling threats, armed Lithuanians broke into our apartment accusing us of having fired from our windows at the columns of the German army. While our house, the marauders satisfied themselves with stealing items of value, which evidently saved our lives; in the at neighboring apartments, they murdered the men and raped the women and girls. In the Slabodke neighborhood, across the Viliya River local Lithuanians carried out a frightful slaughter of their Jewish neighbors, including rabbis.

It is no wonder that in contrast to the Lithuanian masses that packed the streets greeting the German army with flowers, we and our other Jewish neighbors pulled the shutters closed, drew the curtains and locked ourselves in our houses. Apparently, my curiosity won out over my fear and I could not resist from looking outside from a corner of the closed shutter. It became clear to me that the German soldiers entered the city using the same route that the Soviet tanks traversed the year before. Unlike the Soviet army, whose dress was poor and who looked neglected, the outward look of the brightly polished German army was impressive exuding confidence and good health. At that moment, I felt that no army could stand up to an army like theirs and that they were capable of conquering the entire world. Even more so – in light of the acts of plunder, murder and rape carried out that very day by the armed Lithuanian gangs(who called themselves 'partisans'), I found some consolation in the large signs that appeared with the arrival of the Germans, “Wer Pluendert Wird Erschossen – Whoever steals, will be shot to death.” However, very quickly it became clear that this warning did hot apply to the Jews and the Lithuanians continued with their murders, looting and raping in the Jewish neighborhoods and especially in Slabodke. One of the Lithuanian gangs also broke into our apartment claiming that shots were fired at the German army from our house. At a certain point, one of them aimed his loaded weapon at me and there was a very good probability that he was about to shoot. In a loud voice, my mother calmed me down telling me that they would not do anything bad to me. She did this in order to win over the marauders. From that same reasoning, she and my sister repeated the sentence, “After all, they are not criminals …”

Since these gangs especially targeted young men, my parents sent me to my grandfather, Reb

Dovid Levin who lived on a quiet side street. But one day, these bands of intruders arrived at his house. One of them, an armed Lithuanian, bragged about the number of Jews he had murdered and as proof, he showed us their passports that were covered with blood. He tried to drag my 78-year old grandfather as though he was taking him for work. The old man adamantly refused. I acted somewhat as a translator between them. But, he was actually saved by a German soldier whose unit was stationed in the courtyard. I am convinced that had it not been for the reaction of the soldier who became angry, it would seem, by the Lithuanian's breach of law and order, my grandfather would have been shot on the spot or taken by that same Lithuanian to the 7 th Fort (one of the nine fortresses surrounding Kovno) that during those days was transformed into a place of detention, torture and execution for thousands of Kovno's Jewish men and women.

My mother's family from the village of Vekshne (Veksniai), Lithuania. Bottom row, seated left: my maternal grandmother, Paya Wigoder; my Aunt Haya Berzhanski

III. In the Slabodke Ghetto

Events in the Summer of 1941

Along with the respite in murders, looting and rape, rumors increased about the establishment of a Ghetto in the Slabodke neighborhood. We resumed meeting with friends, especially to know how they were doing since the telephones of Jews were disconnected. One of my former classmates, Ella Volpe, who returned weeping from the notorious 7 th Fort, told us of the vicious acts of murder and rape carried out there by the so-called Lithuanian partisans. She also pointed out that the older women mixed water with sand and rubbed it on her face to make her look ugly, distorted or old – so that no one would be attracted to her and cause her harm. She was also one of the very few to be freed from this hell. It is no wonder that the widespread opinion among us was, “It would be best if the Ghetto were set up already; there the Lithuanians would not be able to cause us any harm, at least, we'll live among Jews!.. .”

In preparation for the transferal of Kovno's 30,000 Jews to the Ghetto, a Jewish committee (Komitet) was established to ease, from a technical standpoint, the relocation. Little by little, we dared visit the courtyard of the 'Komitet,' the Jewish committee that started working at Yatkever (Dauksos) Street 24. We wanted to see who were the communal workers who took the initiative at this difficult time. Among them were well-known community figures, such as Attorney Leib Garfunkel, Rabbi Shmuel-Abba Snieg, Attorney Jacob Goldberg and others, who during the Soviet rule were declared 'enemies of the people' and were jailed or confined to their houses.

After the move to the Ghetto, the Committee was merged into the Aeltestnrat – Council of Elders – the organization that with the assistance of the bureaucratic apparatus and the Jewish Ghetto police ran the internal life there.

Among the masses that assembled in the courtyard to seek help in getting a place to live in the Ghetto or to get a dear one freed from the 7 th Fort, if they were still alive, and other similar requests, I overheard a women from the poorer class say, “Why did we speak against the rich when the Soviets ruled? After all, when they had money and food, so did we! Now, when they took everything away from them, what will be with us?”

Close to the sealing of the Ghetto in August 1941, I heard an influential man say to his wife, “I would really like to get a sack of flour for my house.” When we were confined to the Ghetto and the great starvation set in, I remembered that conversation and understood how vital it was. However, I also knew that it was not the most important thing: I learned that that man did manage to get what he wanted at that time, but he with his family was taken to the 9 th Fort, the central location for the murder of the Jews of Kovno.

Commands, Decrees, Systematic Killings (“Aktziye's”), Fear, Pressure and Despair

In the framework of the systematic and massive executions that were known as “Aktziyes” and began to be carried out from the beginning of setting up of the Ghetto, on October 6 1941, most of the Jews who lived in this area were murdered. The Jews called this event the “'Aktziye' of the Small Ghetto.” Only very few, including my family, succeeded in surviving to move to the main Ghetto.

As one who was blessed with the qualities of curiosity and a relatively good memory, I would frequently wander in the streets and alleyways of the Ghetto and soak up with my eyes impressions of the depressing reality into which it seemed that I was unintentionally dropped. Some of the impressions that my eyes saw and that my ears absorbed, I recorded in my mind and also in a special notebook. Thus, I was very impressed by the fact that a very large number of the Jews, including those that were not so scrupulous in their observance, participated in the prayers of the High Holidays. In Hebrew, they are known as Yamim Noraim, usually translated as Days of Awe, but the word Norah can also mean dreadful or terrible. Accordingly, there was a double meaning to the words, Yamim Noraim – Days of Dread, especially in the beginning when the Ghetto was set up. Prayer services (minyanim) were held in private houses, which were in any case, extremely crowded, since several families had to live together in a single apartment. I will never forget the cries and supplications that broke through during the services. I will especially remember Ne'ilah prayer on Yom Kippur; the voluntary cantor was an elderly Jew by the name of Leib Feler (his oldest son, Dr. Noah Feler later served as head of the Sharon Hospital in Petah Tikvah). When he got to the phrase, “Our Father our King, annul the evil decree,” he repeated the word 'annul' many times as his voice chocked with tears and the entire congregation moaned in tears after him. On one of the days of the holidays, in all the prayer houses where services were conducted there was a quick visit by two community leaders, one of them, the former Judge Vulf Lurie who was eventually one of the most powerful and unpopular people in the Ghetto, who came to convince the worshippers to leave immediately for forced labor. The Germans issued the Ghetto an ultimatum to immediately supply several thousand workers to construct a military airfield in Kovno …

My grandfather Rabbi Dovid Levin . My paternal grandmother, Bassia Levin ne'e Rabinowitz

The Time of “Relative Quiet” in the Kovno Ghetto (November 1941 to October 1943

My Thoughts on the Jewish Establishment, the Ghetto Police, Forced Labor and the General State of Morale

A short time after the “Great Aktziye” I was lucky to be apprenticed to the well-known furniture carpenter Mr. Landman. Unlike the airfield, where we worked nearly twelve hours outside in all kinds of weather, I worked for him eight hours in a heated room. I was also able to learn a useful trade in the Ghetto with him.

The author at 17, the age when obligated to do forced labor in the Ghetto

However, after January 1942 when I was 17 years old, I was obligated just like the older men to report for forced labor and was no longer able to be an 'angel.' Yet, nobody fooled themselves into believing that there would no longer be any executions, but this interim period enabled me to explore my surroundings out of curiosity. So, for example, I looked at the condition of people's cheeks, whether they were full or sunken. Thus, I was able to tell who was suffering from starvation. I noticed that the Jewish police and most of the other functionaries looked satiated and even well fed.

I identified fully with the folk songs that sprouted in the Ghetto, like Nit Ayer Mazel – 'No Such Luck,' that expressed strong criticism against the Ya'alehs, the nickname for the 'Big Shots' in the Ghetto. The disapproval against the Ya'alehs focused on their inflated behavior and that they forgot that their high status in contrast to that of the 'regular people' in the Ghetto, was granted to them to a certain extent with the blessing of the homicidal German governor, whose interest they were actually serving. Owing to my careful observation, I noticed that the women were more conscious of their outward appearance even when doing forced labor outside the Ghetto. I remember that even during these difficult days there were people among us who made an effort to go out in the Ghetto streets wearing clean clothing and who greeted those that they knew by tipping their hats, just like free people and not prisoners. This was to prove to ourselves that we still had some measure of control over our own lives. Thus, it was common, even during the most difficult days of terrible hunger, to eat food with a fork and knife, to continue to brush ones teeth and so forth. Likewise, there were some in the Ghetto who tried to wear their Yellow Star of David, which we were required to sew on our chest and back, in an esthetic manner.

Like all the men, I, too, was required to remove my hat in front of the officials at the Ghetto gate when I returned from forced labor. I tried to do this with my head held high. I recall that I would jealously look at the stray cat who could cross the Ghetto barrier without interference. Besides the frustration of being locked behind barbed wire and especially the fear of not knowing what the next day would bring, the torment of constant hunger continued to afflict us. Under the best of circumstances, two or three times a day we ate a watery soup called Yushnik, which was the kind of thing fed to animals. Bread was a rare commodity. Once, my parents sent me to the food distribution station to bring our weekly bread ration, one and a half loaves, home to my family. On the way back, without even noticing it, I inadvertently started to nibble on the half-loaf and then the whole loaf. When I got home, there was absolutely nothing left and to this day, I am still ashamed of it! In addition to the misery of hunger, I felt suffocated living behind barbed wire walls faced by the open rifle muzzles of the erect Lithuanian guards surrounding the wall. Not infrequently, I was haunted by the question, “Is there nobody in the world that knows about us?” I talked about this a great deal. And when I would ask, “What will happen,” the answer would be, “Everything will be fine – for the Jews in America …”

IV. In the Anti-Nazi Underground of the Kovno Ghetto

The Craving for Resistance and its Realization

Just as it was forbidden to bring into the Ghetto food, fuel and, of course, weapons, so bringing in reading material was strictly prohibited. In spite of this, individuals and groups were involved in smuggling. It was done via the gate to the Ghetto or along the wall surrounding the entire Ghetto and guarded by armed Lithuanian guards. Because of the hunger and bitter cold that we frequently experienced in our house, I, also occasionally endangered myself by smuggling food, coal and from time to time, a newspaper – in order to follow what was happening outside the Ghetto, and in particular on the War front. One day I got hold of a newspaper with a picture of a man who was described in German as Bandenfuerer Tito, gang leader Tito and who fought against the Germans in Yugoslavia. I had such a great longing to meet a man like this in the Kovno area! I eventually learned that already in the summer of 1942 the Polish Irena Adomowicz from the Vilna Ghetto secretly infiltrated the Ghetto as a representative of Hashomer Hatzair. The aim of her visit was to encourage the members of the various Zionist movements in the area to increase their organized opposition to the Germans. However, because of the extreme secrecy of her visit, I did not get to meet her, but shortly after I became aware of the active results of her visit. At the same time, I began to hear fascinating accounts of the activities of anti-Nazi partisans in the forests of eastern Lithuania. But how was one able to reach them? When I revealed my wish to some of my close friends in Hashomer Hatzair, I found out that they were already involved in the underground that hoped to attain the same goal. Naturally, I joined the cell of one of those underground groups. Leading the group of three (the troika) was a young woman named Gitta Pogeer, who today is a member of Kibbutz Reshafim. A strange feeling overcame us when one summer evening in 1943, Gitta brought us the bolt of a rifle wrapped in a German newspaper. Even before that, we had heard rumors that there were weapons in the Ghetto, and the stories of the acquisition of arms were passed by word of mouth, but now we were able to feel the cold steel in our own hands! With all of that, we knew that we had to learn quickly how to assemble and disassemble the rifle since another cell was waiting for it. Gitta tested our familiarity and it turned out that she had just learned what she was teaching us yesterday. I was forbidden to reveal my membership in the underground even to my own parents and sister. They probably guessed that I was involved in something serious and important, but they did not discuss it with me. From then on, every aspect of my life was connected to the underground.

The “Estonia Aktziye” – My Watershed Event in the Ghetto

That afternoon, I was sent to a three-story building in the Kovno Ghetto called Bloc C. According to rumor, its basement had an excellent hiding place. On my way there, when I passed by our house, I was shocked to see German and Jewish police forcibly removing my family from their house. The sight of seeing my sister scream bitterly and my despairing father made me want to join them. At that very second, my mother did something that I shall never forget – she gave me an intense look that clearly meant “Get away from here immediately.” And so, I did, without even looking back. That was the last I saw them alive. After the war, I learned that my father most likely perished when the Germans were forced from Estonia in the fall of 1944. My mother and sister who were then evacuated to the Stutthoff Concentration Camp, died of illness at the end of that year.

Of course, I could not have known this when I saw them then for the last time – but at the sight of their hopelessness, I felt in addition to the deep pain also a burning anger that the underground organization was unsuccessful in guaranteeing the safety of my family as I had secretly hoped.

When I reached Bloc C, in mourning and confused, at the entrance I was met by a Jewish policeman, Daniel Birger. I disclosed to him the required password, “Can I stay here overnight?” His response was that he permitted me to enter. Someone removed a cover from the floor and removed some stones that were underneath. Suddenly, I felt that I was sliding downwards until a few pairs of hands led me to a dark room where I could only make out a few lit cigarettes. Within a short time, someone thrust a sandwich into my hands. During the long hours I was there my eyes got used to the darkness and it became clear that along with me in the cellar of Bloc C were a few dozen members of the underground, some of them armed ready to resist their deportation with force. Several times, we heard the voices of Germans searching for people to deport but fortunately, they did not find us. Later our contact people outside told us that the danger had passed. The Germans had already succeeded in locating and deporting the 3,000 required for forced labor in Estonia and we were permitted to leave our hiding place. Even so, we were told, “You are free to go now, but shortly you will have to report to a meeting place, an apartment at Broliu Street 8, since it is very likely that you will be leaving the Ghetto tonight.” From this announcement, I realized that they were talking about secretly leaving the Ghetto for the partisans' forests in the Augustowa area in southwest Lithuania. Thinking about this prospect, provided me with a tiny bit of comfort after a long black day on which I apparently lost forever my parents and only sister without even a suitable shared parting word. I walked stumbling in order to take leave of the green wooden house at Linkuvos Street 56, where my family lived almost from the beginning of the Ghetto until that very day.

I found our house looking as though it had just gone through a pogrom: the doors, windows and closets were smashed and on the floor was a mixture of household items, clothing and food. I had the feeling that someone had already gone through it searching for useful items. Perhaps, it was the neighbors. They received me graciously, but also with surprise. They were under the impression that I was also deported to Estonia that morning along with my family. At that moment, I resolved that come what may, I would never return to this house. I also shared my determination with the neighbors but certainly did not let them know and did not even hint to them about the possibility of me leaving the Ghetto that night. For some reason, I accepted some sandwiches from them and ran as quickly as possible to the assembly point apartment.

The message we got was definitely disappointing: since the Ghetto was still surrounded by an augmented number of German troops, it would not be possible to break through the wall as originally planned for that night. One had to have the spirit to patiently wait until the next opportunity. However, we were already all fired up to leave for the forests. Especially disappointed and crestfallen were those of us, myself included, who were totally alone, bereft of family. As brothers of a shared fate, it seemed like we wanted to remain together from now on under all circumstances – whether we would be able to reach the forests or whether, God forbid, this possibility would again be denied to us. Naturally, some of us, and especially those who had most recently lost their parents, stayed together at the apartment of our friend Penina Sukenik at Broliu 8 Street. More accurately, it was the attic above the apartment that for some reason was known as “The Babilsky's attic floor.” Here, the secret cells merged (the 'troika') and we conducted our lives on a communal basis like the kibbutz preparatory groups before the war. Even so, we hoped that this would only serve as a temporary shelter, since shortly after the Estonia Aktzia, from the end of October through the month of November 1943, the attempts of the underground to smuggle groups in an organized manner to the Augustov forests in southwest Lithuania resumed in high gear.

The Unfortunate Chapter of the Flight to the Augustow Forest

In the passion of the meticulous and thorough planning for this undertaking, the secrecy that surrounded the escape plans was relaxed somewhat and all of us were memorizing the names of the towns and forests located on the route that we would take. Above all, we were apprehensive about how the groups leaving the Ghetto would be made up and who would be in them. The candidates to take part in the escape were chosen very carefully according to their skills and their resourcefulness that would permit them to participate in such a dangerous and difficult venture. Special care was taken regarding the participation of girls. Each participating youth movement was permitted a small quota of girls and the final decision was up to the members each individual movement.

In keeping with this agreement, Hashomer Hatzair was permitted to choose four out of the fifteen young women who presented themselves as candidates. I remember as though it happened today, the dramatic meeting with twenty-five senior members of the movement participating gathered around the stub of a candle in Babilsky's attic as we agonized on how to come to this fateful decision. First, it was thought that the contenders should be divided according to certain indispensable criteria – Aryan appearance;* fluency in the Lithuanian language; physical endurance and a familiarity with their surroundings. This was truly a fateful deliberation and all those involved felt it. The lead discussant, Ali Rauzuk, the head of the chapter, and Moshe Petrikansky, the head of the combat units, attempted to explain in a rational manner the need for making the awesome decision that very night, since the following day they had to submit the names to the underground leadership. At variance with them were those who favored the candidacy of one person over the other also from an emotional standpoint, such as Moshe Elionsky who took up the cause of our friend Rachel (Koka) Rozental who was the only one of her family still alive. “Koka must be among those going,” he cried in bitterness while the rest lowered their tearing eyes. Bilhah Markus responded with a deep sigh when her turn came to speak. And what was she to say? She did not have any of the requirements needed for a young woman to be sent out on the dangerous and complicated mission. Suddenly, I heard my own voice protesting my exclusion from participating at this stage because of a broken right ankle that had not yet healed adequately. “I'll limp after you with my broken foot if you leave me behind!” Very slowly, they all left to go to sleep and the four pleased young women, Hana Simon, Miryam Eydels, Mira Buz and Rachel (Koka) Rozental, did not know whether to rejoice or to cry. Conversation faded along with the candle stub and depression hung in the air. Beginning with the next morning after that critical night and for the days following, the “lucky ones” who were chosen left us for the forests of Augustow, while I and several of my friends who were rejected continued to live at the same place. Over time, additional Hashomer Hatzair members and others joined us.

Still, almost every day alarming Job-like reports about the terrible fate of the dozens who left for the Agustov forests reached us. A large number perished at the hands of the Lithuanians who ambushed them on the roads; the others returned to the Ghetto dejected and bewildered and only two succeeded in reaching the desired objective. They were Shmulik Mordkovski, a member of the Young Pioneers (Hehalutz Hatzair) and Nehemia Endlin, from the Antifascist Fighting Organization (the Communists). However, once they reached the goal, they found no trace of the partisan base they had been assured of by the heads of the Communists both inside and out of the Ghetto. To our great sorrow, we learned that among those who died in the venture were six of our finest colleagues Moshe Elionsky, Benjamin Volovitzky, Leo Ziman, Nahman Levin, Arie Mitzkun and Jakov Strasburg

In the Kibbutz – Mildos 7

Stunned and depressed by the appalling failure of the Augustow venture in which we lost the finest of our colleagues, it was only natural that we cut off the organizational link with the communists, or as they were known in the Ghetto, Antifascist Fighting Organization. Their leaders were responsible for planning this failed endeavor. With this, we drew even closer to the Socialist Zionist camp in the Ghetto. As a result, we, along with some members of Dror/Ha-chalutz Hatzair moved to a four-room shed on Mildos Street 7. This residence was called “Kibbutz Mildos 7,” and it along with its social and cultural activities functioned on a collective basis modeled after the Kibbutzim of Eretz Yisrael. The names of the members who lived there on a permanent basis as well as those who still lived at their previous apartments are listed on page 187 in the book by Zvi Brown and Dov Levin, The Story of an Underground – The Resistance of the Jews in Kovno [Lithuania] in the Second World War, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1962.

On occasion, we arranged political-ideological discussions and evenings of group singing. Among the popular songs that became a hit with us were Around the Bonfire by Ya'kov Orland and Hey Harmonica. With great enthusiasm, we danced the Hora and other folkdances. It should come as no surprise that in the Ghetto our apartment became the desired gathering place for all who longed for vibrant social life. It reminded one of the dynamic Zionist pre-war public functions and the festive meetings and activities we conducted to mark cultural and national events in the optimistic atmosphere for those who would be fortunate enough to be among those able to go on Aliyah to Eretz Yisrael. Among the visitors were remnants of the Socialist Zionist leaders and activists, some of whom assumed official positions in public sector and administration of the Ghetto. One of them was the policeman Hirsh Fridman who took part in the deportation of my family to Estonia. When I mentioned this tragic event to him, he was very agitated, and apologized that no one had told him that he was dealing with the family of a member of the underground. True, I had known earlier that members of the underground served in the police force and were required to carry out orders of the ruling powers, but since this personally affected me, it was even harder for me to accept this two sidedness. Anyway, my negative attitude to the Ghetto establishment increased even more.

Except for this painful episode, the three months I spent at 'Kibbutz Mildos 7' were like a warm spring in the somber reality of the Ghetto. More than that – our kibbutz was actually run on the model of the preparatory kibbutz of pioneers ( halutzim) getting ready for their future in Eretz Yisrael. Given our circumstances, the immediate goal was changed from Aliyah to Eretz Yisrael to reaching the partisans' forests. At this time, that goal was more or less attainable, especially for the young men among us, thanks to the newly opened opportunity of getting to the Rudniki (Rudninkai) forests in the Vilna area. Unlike the unfortunate and failed attempt to reach Augustow that was carried out almost completely on foot, this undertaking was motorized by way of trucks. The objective was also closer, distance wise, Rudniki forests in the Vilna area. However, it became clear that the chances of the young women in our group, whose number was far greater than that of the young men, to go to the forests was very slight compared to the communist women. The communists, through their non-Jewish colleagues outside of the Ghetto, maintained good contacts with the partisan command in the forests. It was no wonder that in the Ghetto the impression was that the Anti-fascist Fighting Organization, that is the communists, held 'the key to the forest' in their hands. Whether we are speaking of the actual impression or an exaggeration out of all proportion, it was clear to us that the leadership of the organization controlled the make-up of the groups going to the forests. Generally, this was not spoken of in public, but from our friend Ali Rauzuk, the acting head of the Hashomer Hatzair club in the Ghetto, we heard that a bitter struggle went on over the composition of the groups going to the forest, with “the communists insisting that their opinion should be the deciding factor in their make-up.” Indeed, in one case when one of our members, Roza Strashuner was chosen to go to the forest and even passed through the Ghetto gate with her personal gear to join the others, was pushed aside in favor of someone else, a relative of the owners of 'the key.' Within a few days, arrangements were made for a small number of the girls in our group – Mira Buz, Penina Sukenik, Koka Rozenthal and Rachel Zagay – for hiding places in the villages thanks to the most valued initiative of Dr. Pessia Kissin. Only one of our female members, Gitta Pogeer who was part of our kibbutz, was privileged to get to the forest and join in the effort to fight against the Nazis and their local collaborators. One of our most esteemed members Shmulik Mordkovski, who succeeded at the time to reach Augustow, left for the forest even earlier, not in accordance with the 'key,' but thanks to his exceptional ability to reconnoiter and guide. The first to be chosen by the kibbutz to go to the forest were Barukh Grodnik (Goffer), Hayim Gekhtel (Galeen), Jakov Susnitsky, Gitta Pogeer (mentioned above), Yankel Kave, Josef Rosin and Grisha Sheyfer. On the occasion of their departure, 5 February 1944, the kibbutz had a festive 'going away party.' We sat around tables set with tea and candies, produced in the Ghetto. We reminisced about their participation in the group, the summer camps and the various gatherings we had. We sang some of our movement's songs that were recorded in the notebooks of one of our longest standing members, Yerahmiel Voskoboinik. Our leader Ali Rauzuk delivered the 'message of the movement.' The party reached its climax when in a festive ceremony in accordance to the tradition of the movement, a red flag was brought in and the seven members who were going out to the forest heard 'the movement pledge.' As though it were a message from another world, the following words echoed: “To be loyal to my people, my language and my homeland and to fight for freedom, friendship and justice in human society.” The experience filled evening ended with singing and dancing.

I also experienced the same expression of warmth and friendship from my colleagues when after a month my turn finally came to leave along with fellow kibbutz members Zvi Brown and Josef Melamed to join the partisans in the forest. Nevertheless, I still had to solve the problem by myself of getting a rife as a precondition for leaving. To do so I did not hesitate to sell my wristwatch, a prized Tissot that I had gotten at the time from my Uncle Moshe Levin for my Bar Mitzvah.

Standing, left to right: Uncle Moshe Levin, Aunt Rivka Guttman nee Levin, Uncle Shabtay Levin. Seated, left to right: Uncle Gershon Levin, Uncle Benjamin (Hone), Lewin, my Father Tzvi Hirsh Levin

Like many in the Ghetto, I kept a daily personal diary, which I called “Chronicles” in which on an almost daily basis I wrote down what happened to me. I included in it idioms, folklore, jokes of the day as well as news from the war fronts that I gathered from various sources. Before leaving, to join the partisans I was going to turn over my diary to my good friend Rivka'le but she suddenly was taken to a work camp and the diary was lost.

Meanwhile, preparations including training exercises began. We were equipped with appropriate clothing and weapons. This continued for several weeks. The head instructor was Nehemia Endlin who already had acquired experience in the partisan forest and he taught us the rules of fighting in enemy territory. The end of training was marked with a party held in the shed of the Anti-fascist Organization who was in reality communist. One of their leaders, Hayim–Dovid Ratner overbearing speech on “our role as Soviet partisans … on our duty to sacrifice our blood in the holy war against German and international fascism.”

Suddenly, our colleague Zvi Brown got up after requesting permission to speak and said the following in our names:

“We are joining with the Soviet partisans and we will fulfill faithfully and sincerely every task we are assigned as partisans. But we will not forget, even for a moment, that we are doing this as Jews; as people from the Jewish Kovno Ghetto in order to revenge the blood of our brothers and sisters, our mothers and our fathers who were slaughtered because they were Jews and we will avenge the honor of our people who were murdered …” There is no way of knowing whether or not these words pleased the heads of the Anti-fascists, but the impression was that a large portion of those present identified with them.

Our day of departure was delayed several times and we began to think that it was a dream that would remain unfulfilled. The long hoped for day arrived – 7 March 1944. In the evening, the three of us took leave of our friends in the kibbutz apartment Mildos 7 with the traditional words, “Until we see each other again in Eretz Yisrael.” These were the last words we heard from those who remained behind to face their fate. In our innermost thoughts, we nurtured the dim hope that on the Day of Judgment they would be able to save themselves by means of the 'malina' the hiding place that they dug under the kibbutz apartment.

However, these thoughts immediately gave their place to what was in store for us in only a few minutes at the meeting place near the gate of the Ghetto for those who were leaving. After a short while, we were ordered at that place to get on a truck that had parked outside the Ghetto gate. I was incredibly surprised when I detected that there were two uniformed German policemen with weapons on the tailgate of the truck. Only after a few minutes did I realize that the two of them, Josef Melamed and Katriel Koblenz, belonged to our group that was leaving. Their assignment was to serve, as it were, as guards escorting us. More so, the electric lights near the gate suddenly went out and I understood that this was a clever ploy of our people to insure that the guards at the gate would not be able to identify us. At that moment, my estimation of the leadership of the underground deepened because of their astute and adept planning and my hope was that this would also be so in the future and that we would not be caught. While we were already sitting crowded into the truck, along with the noise of the motor we heard thatsomeone at the gate, a policeman or someone else ask “Where are you going.” Another voice answered that the men were on their way to work in the town of Babtai. Actually, the truck did not take us to that work place but went in an entirely different direction – that is to the thick forests of eastern Lithuania in the Rudniki area, some 20 kilometers south of Vilna. That was the headquarters of the partisan group known as “Death to the German Occupiers,” whose ranks we eight women and twenty men were on our way to join. During its existence, this unit and its offshoots absorbed close to 150 fighters from Kovno Ghetto. About a third of them fell in battle. At one point at the beginning of the trip, we were ordered to remove our Yellow Stars of David from our clothing and to load our rifles with five bullets. After the command was carried out, we were told in a most decisive manner, “From now on you are partisans.” And, indeed, these words were not uttered flippantly.

V. In the Ranks of "Death to the German Occupiers" Partisan Unit

(As Though on a Different Planet)

To the Forests

The difficult trek until we reached the Rudniki Forest on foot from the place from where we got off the truck lasted two nights. During our march through the swampy area among huge trees the like of which I had never seen in my lifetime, I imagined that each crack in the trunk of a tree like each broken bough leaning to one side or the other were 'predetermined signs' meant to make it easier for the partisans to find their way in this mysterious jungle, which was really the 'source of sustenance' for them.

The voice of Nehemia Endlin, our guide, quickly ended my daydreaming by declaring that we were already getting close to the main guard-post of the camp where 'our' unit was located. To our great satisfaction, it turned out that the guard at the post was none other than our colleague Yankel Kave. He held a sawed-off shotgun in his hand and gave smiling jealous glances at our very impressive weapons and equipment. A second later, he was almost knocked over when inundated with a torrent of hugs and kisses from the newcomers. Our hearts united at this moment and I even was kissed swiftly by Peretz Padisson a former officer in the Ghetto police. Our relations in the Ghetto were not good but this was a time of goodwill. The newcomers symbolized for the 'forest veterans' the home and family existence that they had come from and who knew if or when they would be privileged to ever see either of them again.

The author in the forests of the Partisans

For the first two days after we arrived, I could not stop staring, as if to swallow with my eyes everything in the compound of the camp. I went out joyfully in the morning to wash in the water of the Merechanka stream and I visited every dwelling hut, except, of course, for that of the commandant. I was summoned there for a 'getting acquainted meeting' and like all the new fighters I was required to fill out a complex questionnaire, according to the Soviet practice. On the third day my integration into the fighting force began and at first I was assigned to the 'combat unit.'

However, at this point, a surprise awaited me. The partisan, Dovid Sandler, who knew about my broken right ankle in the Ghetto, apparently felt it only correct for humanitarian reasons to reveal this fact to the command staff and as a result my first assignment was cancelled and again, I returned to being a rank and file 'common fighter.' When I objected to this order, veteran experienced partisans advised me to accept the decision, since no one knew what fate had in store. Be that as it may, afterwards, I participated in all kinds of combat and other assignments that required more than once to go on marches of over 35 kilometers and I measured up to the challenge.

No less than the physical effort required to carry out flawlessly what was required of us from a military standpoint, I had to learn how to react to verbal and other insults from our non-Jewish comrades. Most if not all of them arrived in the forest after escaping from German captivity and it was there that they were infected with the anti-Semitic virus. In one case, it almost cost me my life.

This is what happened: On one of the first requisition missions I participated in, heavy snow fell and we had to use sleighs that we confiscated from area farmers. In the middle of the journey, it became clear that we made a directional error and we stopped for a few minutes to consult. We took the opportunity to get off the over-crowded sleighs to stretch our legs. When the order to move-on was given and I tried to climb back onto the sleigh, one of the veteran partisans of the unit violently shoved me and in a split second, I found myself futilely chasing after them. Having no choice, I stood in the frozen snow with rifle in hand calling out for help while a snowstorm mixed with the howl of wolves whirled around me. In spite of the hopelessness, it seems that my cries were heard for at some point I felt a hand on my shoulder and I heard, as if in a dream, words of encouragement in Yiddish: "Come with me, you are lucky!" It was the partisan, Leyzer Tzodikov, an acquaintance from the Kovno Ghetto who was the only one of all those on the sleigh who noticed my absence. He demanded that they switch direction and search for me until they located me in the area. At that moment, I found in that act the value of Jewish solidarity but I also learned the lesson that you cannot rely on all your comrades in combat.

In spite of the difficulty in adjusting to the conditions of the partisan forest and the reality in which nearly every day one of our colleagues was killed in skirmishes with the Germans and their Lithuanian allies, I was happy that I was finally able to defend myself with weapon in hand and wreak vengeance on the enemy. Even more so — while a portion of the Jewish fighters, especially those who were members of the communist party or its youth movement Komsomol, had exaggerated expectations concerning the attitude of their fellow non-Jewish partisans and were bitterly disappointed by their anti-Semitic inclinations, we veterans of Mildos 7 who did not share their false hopes to begin with and who nurtured amongst ourselves our Zionist beliefs, were less offended.

However, for very clear reasons, those eleven of us who came from Kibbutz Mildos 7, known in the forest as Shomrim (adapted from the name of their youth group Hashomer Hatzair), were very cautious, like keeping away from fire, not to emphasize our ideological distinctiveness and certainly not to maintain an organizational framework. Amongst ourselves, we continued to develop our close and devoted relationship especially providing mutual help in time of stress. Generally, we kept our meeting with each other on a low key. Likewise, we were very careful not to utter a superfluous word, even in Yiddish, to avoid offense.

Nevertheless at the same time, we tried as much as possible not to deceive and avoid being seen together at the frequently held evening bonfires held in the center of the camp. In the atmosphere of camaraderie that pervaded, two of our fellow members Yankel Kave and Gitta Pogeer stood out with their solo performances of Yiddish and Hebrew songs. I tried my luck by playing tunes of Eretz Yisrael, such as The Beautiful Nights of Canaan on the alto recorder that had miraculously been with me since my participation in the student orchestra in Kovno's Hebrew Gymnasium.

Faithful to the tradition of Mildos 7, our comrade Josef Rosin played Russian and Hebrew tunes on his harmonica. Some of them, such as Hey Harmonica and Around the Burning Bonfire, became 'hits' and more than once swept the crowd into dancing a spirited Hora. We also found among our colleagues in arms Jews who did not hide their anger that we sang Hebrew songs.

At a certain point, we developed a very close relationship with our fellow members of Hashomer Hatzair that fought in the ranks of the Vilna units in Rudniki forests. We knew some of them from the time they visited our group in Kovno immediately after the takeover of Vilna by Lithuania in the end of 1939. Most of us, and especially our comrades from Poland like Zvi Brown and Hayim Galeen, heard many and some confidential things about the personality of the head of their Hashomer Hatzair chapter Abba Kovner, who at this moment acted as the real leader of the Vilna units. But, how were we to get to him to have a heart-to-heart talk with the leading personality of the movement.

As it turned out, just as we were anxious to meet with him, he was making every effort to meet with us far from the prying eyes of the slanderers both Jews and non-Jews among them and among us. The hoped for meeting took place sooner than we had thought possible and under circumstances other than we had thought. This is what transpired.

The Dramatic Meeting with Abba Kovner and Its Consequences

One clear day in April 1944, when my friends from Kibbutz Mildos 7 Hayim Galeen, Zvi Brown and I were standing at the main guard post of the unit at the edge of the camp, suddenly a man riding a white horse appeared on the way to the guard post. When he got closer, I was able to make out a pale young man with a black pompadour in a dark uniform, wearing heavy boots armed with a sub-machine gun an old pistol and a map hanging on his belt. For some reason the three of us guessed his identity even before he stated the password. One of us asked him his name and the purpose of his visit in order to inform the officer on duty — and our conjecture proved correct. It really was Abba Kovner in person the commander of the Vilna units that we heard about while we were still in the Kovno Ghetto and whom we had hoped to meet with for a long time.

As we were shaking hands, we presented ourselves as members of Hashomer Hatzair and we were exchanging news about the fate of mutual friends in the Ghettos of Kovno, Vilna, Bialystok and Warsaw. He wanted to know about the attitude towards the Jewish fighters in our group. From the gist of what our guest said, we learned the official reason why Abba Kovner visited our unit. His purpose was actually to meet with us as members of the movement (Hashomer Hatzair) with all that that implied.

Naturally, we shared the news of this meeting with our members keeping its taking place top-secret. From then on, our relationship with the movement members in the Vilna group became stronger. The designated contact-people were Barukh Goffer, from the Kovno group with Ruczka Korczak and Zelda Tregger from the Vilna group. We got from them for a quick reading a copy of Iggeret L'haver (A Missive to a Member) that Abba Kovner had written in the Rudniki forest in March 1944.

The Missive — Its Contents and its Significance

The 46-page missive included up to date information in Hebrew and Yiddish on the activities of the underground under German occupation in the Vilna Ghetto and other places in Eastern Europe as well as strong condemnation of anti-Semitism even in the partisan controlled forests. In a detailed accounting of the Soviet Union on its hostile attitude toward Zionism, the letter also hinted about the need to organize illegal immigration to Eretz Yisrael from among the remnants who would survive in the areas of Lithuania and Poland. I recall that when the missive reached my hands, I was especially moved by the final words, "Be strong and courageous for battle and for revenge." It reminded me of our movement's newsletter from 'the good old days' before the war. I also understood very clearly that from the standpoint of the partisan leadership and the representatives of the NKVD (the Soviet secret police) in the forest, this was anti-Soviet material that endangered the lives of anyone who touched it. It is no wonder that I felt that I was holding a 'hot potato' in my hands or even a hand grenade with its pin removed.

Therefore, I cannot forget Gitta Pogeer my comrade in arms and in the movement, when she handed this top-secret notebook over to me in the partisan dug out of our unit. She made me swear to return it only to her personally, lest everyone else would devour it. When I was able to get away to the densest part of the forest and started to excitedly read what he had written, it was as though I held in my hands one of the stenciled bulletins from the leadership of Hashomer Hatzair. It seemed that the only missing thing was the opening "To the members of Hashomer Hatzair in the forest, Be Strong!"

I am not embarrassed to admit that even today when I think about it, I feel something like chills up my spine, about the youthful excitement of those years - how cautious we were even when speaking among ourselves about that notebook. We could not deny its existence or the feeling of satisfaction and confidence it inspired among us. For in addition to the image of connecting to the nostalgic past, we received group reinforcement of the 'us' against the 'others' in the inflexible military framework and the alienating reality in the forest that emitted waves of anti-Semitism that could even be fatal!

We were especially encouraged by the sections in the missive that related to the communists and the members of their youth organization, the Komsomol. We now had the ability to "know how to answer" their arguments. Even in our unit, we were reluctant to speak to them openly.

They certainly did not reveal the details of their discussions held in the framework of closed cell meetings with the participation of the anti-Semitic commissar. There they covered in utmost secrecy items that affected all of us including carrying out death sentences against Jewish comrades in arms. We now delighted ourselves with the knowledge that we, too, had our own secrets. THE secret that warmed our hearts the most focused on our hoped for vision that was explicitly mentioned in the pages of the letter — Aliya and/or Bricha (Escape) to the Land of Israel.

Only after the letter was passed hand-to-hand with the respect usually reserved for a holy object and returned, as we were required to do, to our Vilna colleagues, were each of us who were privileged to study it and to digest with greater spirit able to evaluate its importance and significance. We found out that Abba Kovner wrote this epistle in Hebrew and Yiddish on forty-six pages of a notebook in the middle of March 1944 when all of us were already in the forest. It was akin to a summary of the platform of the FPO (Fareinigte Partizaner Organization), the United Partisan Organization in the Vilna Ghetto. The FPO for us was somewhat of an enigmatic group about which we had up to that time only fragments of information. But far more important and relevant for our purposes and the section that was most conceptually informative were the lines that provided a kind of ideological manual meant to capture the ranks of the remnants of the Zionist youth among the partisans. The objective was that when the time came the surviving Jewish remnants would join with them to go to Eretz Yisrael — the hope for Aliyah to Eretz Yisrael was the most longed for aspiration that from our earliest youth we hoped to accomplish. As far as I recall, the primary need we saw at this point was to internalize and teach ourselves those sections of the letter that dealt with ideological and moral values that could be attained even in the harsh reality of the partisan forest. We also wanted to share our opinions on the operative directives embodied in the text that related to the reality if and when we would merit to see the day when we would leave the forest.

Truly, our hearts yearned for that day. But, as one who for more than two years was a close-up eyewitness to the vicious murder of most, if not all, of Lithuanian Jewry, we did not delude ourselves that when we would return to our homes, we would find our loved ones there. Even so, there were among us those who in the depths of their hearts secretly nurtured some hopes — in spite of it all, perhaps, maybe? With the state of things being what they were, I was not open to the thought that if I would survive fighting with the partisans, that I would volunteer to continue fighting, as it was clearly stated in one of the chapters of the letter that dealt with what was expected to happen with the arrival of the Red Army.As this was the state of things, I was not open to the suggestion that if I would survive fighting with the partisans, that I would volunteer to continue the battle, as it was implied in one of the chapters of the letter where it discussed what was likely to happen with the arrival of the Red Army.

There is no need to add that from the entire spectrum of directives and propositions, whether they were stated resolutely or whether they were hinted at, I was drawn with great enthusiasm to every word in the letter that had any connection with the fulfillment of the dream of Aliyah to Eretz Yisrael. Subtle reminders of this subject, such as 'wait for instructions,' we got even in passing conversations that took place with Ruzcka Korczak and Zelda Tregger, members of our organization who were in the Vilna units. It is no surprise that as the days went by and the columns of the Red Army advanced closer to our area, our hopes increased.

VI. Exiting the Forest and "Self Evaluation"

On 7 July 1944 when the thunder of gunfire signaled that the battles between the German and Red armies had reached the edge of the forest, the hoped-for order for all the partisan units to move northwards with the goal "of liberating, united as one, with the soldiers of the Red Army the capital of Lithuania — Vilna." The news spread very rapidly throughout the forest. Very few of the partisans closed their eyes that last night in the forest and did not join in the spontaneous expressions of joy — singing, dancing, drinking and firing guns in the air. For the Jewish fighters who were also swept into the general celebration, this night was also a night of "self-evaluation" and the severe dilemma raised by questions like, "where was he to go and who would he find?"

On the night of 8 July, with the beginning of the feverish preparations for leaving the forest for the direction of Vilna, Ruzcka appeared in our unit of the camp. As mentioned above, she served as the liaison and secret courier to us (the Kovno Hashomer Hatzair group). Through her, Abba Kovner communicated to us regards, words of encouragement, information, various instructions and also his missive. This time, Ruzcka came to us on an emergency mission — that is to give us instructions dictated by the decisive hour soon to arrive, that is, the hour of liberation. In anticipation of this, she had some orders and these focused on the topic that at that moment appeared to us in a dream and along with that like the first step in the fulfillment of the vision alluded to often in the his letter concerning Aliyah to Eretz Yisrael. Ruzcka's unexpected arrival was a sign that the vision was on the way to becoming a reality. We were also persuaded by her instructions, both laconic and determined, that required us to be concentrated in large population centers, to maintain unbroken communication amongst ourselves and to wait for further instructions.

This top-secret item continued to warm our hearts when we had the good fortune on our way to Vilna to encounter the first Soviet soldier after three years of hell. He was a member of a tank crew, dusty and covered with soot but smiling and waving his hand at us. Our hearts were overflowing and many of us ran to kiss him. More soldiers came in vehicles and on foot and my gaze, for some reason, focused on one of them with a pale face and moist eyes — certainly a Jewish solider! He came from a Lithuanian small town from which he managed to escape in the summer 1941 into the interior of Russia and from that time, he served in the Red Army. Now he was hoping to meet someone from his family and he asked us about the chances. We shook our heads and were silent. Somebody burst into tears. He lowered his personal rucksack and distributed its entire contents to us. "Take, my dear ones, to your health!" We shook hands and he climbed onto his vehicle and he disappeared into the distance. We continued with heavy hearts on our way to Vilna, surrounded by flames and battles. In one of them, three of our group fell. On 13 July 1944, after emotional meetings with soldiers of the Red Army, within the framework of our unit we entered the center of Vilna where street battles were still going on here and there. Of the tens of thousands of Jews who at one time filled the Jerusalem of Lithuania we came across a few dozen thin and pale "living skeletons" who peeked from hiding places — brands plucked from the slaughter. We were given orders to police the area and clear it of the enemy. After a few days, we were ordered to turn in our weapons.

With this, not a moment went by without us being concerned for those who remained in the Ghetto. Our fear for their future especially increased. We later found out that on 8 July 1944, when the order was given to leave the forests and join with the units of approaching Soviet army, on that very day the remnants of the Jews in the Kovno Ghetto were being hastily deported to concentration camps in Germany. When we finally reached liberated Kovno in the beginning of August 1944, bitter disappointment awaited us. I wrote the following excerpt in my diary:

"While around us were still heard the cheering and celebration of the victorious Red Army advancing rapidly to the west, we were escaping from ourselves. Is it possible to eat of the sacrifices of the dead? The storm of battles and tempest of conflict had ended; the thunder of the mortars quieted and now came a thin silence. Each one who escaped alive did a self-evaluation. There were those who discovered that what was lost was overwhelming and despair increased … We former partisans were accustomed to living together and this habit stuck with us. We meet and eat together and carry on conversation but the end of every discussion, no matter what topic it started out on, was the same. Where to? Even with all of our gratitude to the Russian people and for their future wellbeing, most of us could no longer walk on the ground that was drenched with blood. The group from Mildos 7 and their colleagues came together again. The bond that developed in the forest with our friends from Vilna was firm and enduring. We were at one with the determination, even if we did not openly express it that the goal was — ALIYAH.

We were liberated from the reign of terror with its nightmares but nothing else. We returned our guns satiated with revenge. But who could free us from the heaviness in our hearts, the atmosphere of bereavement and the loss of parents that gazed from every street corner and shrieked from every clod of earth? At first we envied our Vilna colleagues who already returned home, so to speak. At 'home' they only found some five hundred emaciated and pale Jews who rushed out of their hiding places.

They were survivors who were saved from a tremendous conflagration. When we heard that Kovno was liberated we rushed there as in a frenzy. Everyone went to his/her own house with trepidation and fear. We went to our house, Mildos 7 — a pile of ash with burnt bricks. This is all that is left of the entire house. In the smoldering pile we found torn pieces of paper with accounting notations and a lists of food supplies in Hebrew. A blue sign covered in enamel with the number seven written on it gleaming in its whiteness as though it was demanding recognition for the house that once stood on this spot. The long shadows slowly dissipate. Very slowly the light of day pours over the face of the earth but most of us can no longer step on this blood soaked earth. There is only one possible goal, even if not expressed — ALIYAH TO ERETZ YISRAEL.

VII. Epilogue

The advancement in stages towards realizing our goal of Aliyah, or more correctly escaping southwards from Soviet Lithuania in the direction of Eretz Yisrael, started in the first weeks after we left the forest. Even the sympathizers with the Soviet regime among us were aware that such plans were considered activities threatening to the state if not actual treason.

Therefore, we had to keep them to a minimum, carefully and secretly, just as before in the forest. That is, at this stage we could only share the idea. The secret operations committee was basically composed of the remnants of the political organizations that joined in anti-Nazi activities in the Ghetto, naturally, without the communists who we distanced ourselves from as one would from fire.

On the other hand, it was not possible for me not to reveal the secret to my friend from childhood and school Abrasha Yashpan, who to my great surprise and delight returned from the front with decorations of merit, but also with battle scars. He endured a period of wandering and hardship until he was accepted in the first-rate Panpilov Corps of the Red Army under the new name of Artiom Semionovitz Jashpanov, indicating that his parents were Russians of Lithuanian background. Thus, he was quickly taken into the higher command of the Soviet administration in Lithuania. I had to work on him day and night in order to remind him who he really was. I reminded him about how we parted by a dramatic telephone conversation as the Nazis invaded Lithuania in June 1941. In the end, not only did he resume speaking in Hebrew to me, but he enthusiastically joined our forces with all his heart.

As the senior deputy to the head of the committee of the peoples' commissars of Lithuania, he had unlimited control over the issuance of travel orders (komandirovka) and movement permits stamped by government ministers. Obviously, these passes were distributed to our colleagues in utmost secrecy who were preparing to move southward in the direction of Romania to 'catch' a boat sailing to the Mediterranean Ocean.

In my modest apartment on Raseiniu Street 3, where we lived together, we would host our friends or just plain Jews who survived in Lithuania and who wanted to get out of here any way possible. Those who seemed sincere, we helped and that with a permit from the secret actions committee. What our many visitors did not know was that behind every picture hung on the walls, secret instructions were hidden along with the code names of contacts and travel certificates that could be used anywhere in the Soviet Union. Practically every visit from old-time friends and generally anyone else spontaneously led to a friendly get-together as it should be with plenty of alcohol and Hebrew songs. Almost every guest would write down for us as a memento a few words, according to his ability and his frame of mind. Nonetheless, the path to the fulfillment of the exciting plans to escape from here to Eretz Yisrael was not a bed of roses.

Soviet sentries opened fire at the border crossing between the Ukraine and Romania causing fatalities. Among those arrested were my colleagues from Kovno already mentioned, like Gitta Pogeer, who still has the table cloth she embroidered while in jail bearing the words "If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither," Psalm 137:5 and Abrasha Yashpan, who astonished us again with his ingenuity. At a trial that took place 19 April 1945 in the military court in the city of Chernovitz he pretended to be a madman and succeeded in not only concealing his real identity but he convinced the judges of his simplistic version of events - that he just happened to be at that place by accident since he wanted to buy nails. I found out about all of this when we were reunited after he was released and reached me in Bucharest. There was no end to my exhilaration since all during the time he was jailed I had trouble sleeping worrying about his fate. I felt guilty since it all happened because I was the one who got him to return to Judaism and Zionism and because of this, he was paying a high price.

Compared to his experience, my journey southward was relatively easy from the time when I left Vilna on 17 January 1945 using the documents that Abrasha Yashpan prepared for me stating that I was traveling to buy dried fruit in Chernovitz for a particular factory in Kovno.

The journey to Eretz Yisrael stretched out to almost a year, since I frequently had to make stops, change the route, travel by car, on foot, in trains and on the roofs of trains and change as needed my real and forged travel permits. Repeated below

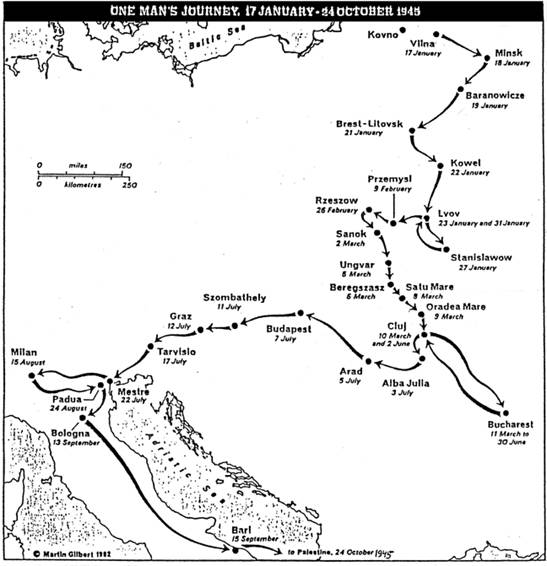

Since I kept a diary at that stage of my life, I am able to provide a very accurate account of the roundabout nature of my wanderings both chronologically and geographically. A map depicting this journey is presented in Martin Gilbert's book Atlas of the Holocaust and is called "Way of One Man."

The Map of the author's journey to Palestine (1945)

The Soviet Union (USSR):

.....Vilna — January 17, 1945

.....Minsk — January 18

.....Baranovitz — January 19

.....Kovel — January 22

.....Lwow (Lemberg) — January 22

.....Stanislawow — January 27

.....Lwow — January 31 (returned because of incarceration of comrades in Chernovitz)

The author (standing on right) with his journey companions, Masha and Isser Gail and others, Lvov (Lemberg), January 1945

Poland:

...

Przemysl — February 1

...Jaroslaw — February 12

...Rzeszow — February 26

...Lublin & Rozwadow — February 27

...Rzeszow & Krosno — February 28

...Rymanov — March 1

...Sanok — March 2

Carpatho-Russia:

...

Humenne — March 3

...Chop — March 4

...Uzhgorod & Munkacz — March 5

...Gati, Beregszasz & Shevlius — March 6

Romania:

...

Halmi — March 7

...Satu-Mare — March 8

...Oradea-Mare — March 9

...Cluj — March 10

...Bucharest - March 11 to June 30

...Cluj — July 2

...Alba Julia — July 3

...Arad — July 4

The author (on left) reunited with Abrasha Yashpan, after release his from a Soviet prison, Budapest, July 7, 1945

Hungary:

...Budapest — July 7

...Shombathely — July 11

...Shengothard — July 12

Austria:

...

Folsdorf — July 13

...Graz — July 15

...Kefllach & Lankowitz — July 16

Italy:

...

Tarvizo — July 17

...Mestre - July 22 to August 14

...Milan — August 15

...Padua — August 24

...Bologna — September 13

...Bari — DROR Camp - September 15 to October 15

...Illegal Immigrant Ship — Pietro 2 — October 16 to 22

Eretz Yisrael:

...

Rishpon-Shefayim Coast — October 23

...Givat Hen — October 24

...Kibbutz Ma'anit — October 24

...Kibbutz Beit Zera — October 26

First day in Kibbutz Beth Zera .

The small fishing boat, Pietro 2 on which I sailed along with 171 other illegal immigrants whose backgrounds were similar to mine, left the southern Italian port of Taranto on 17 October 1945. We arrived at the coast of Shefayim, which is in central Eretz Yisrael on the night between the 22 nd and 23 rd of October 1945, without being caught by the British police that lay in ambus for illegal immigrants without entry papers.

With my friends from Mildos 7 at our first swim in Lake Kinneret.

Along with a fair number of my friends from Ghetto Kovno, I settled at Kibbutz Beit Zera in the Jordan Valley. The veterans of this Kibbutz settled in Eretz Yisrael before World War II. We were greeting with warmth and love as we symbolized to them their young relatives who had perished during the Holocaust.

My first visit to the first Jewish city, Tel-Aviv (December 1945).

Like the rest of the survivors of Ghetto Kovno who were of draft age in 1947, our group participated in the War of Independence.

The author doing military service

Since then, we met annually, usually during the Sukkot holiday, and we reminisce. It was natural that over the years these annual meetings developed into both joyful and educational events for our children who eagerly devoured the stories of what happened to us during the war and the hardships we endured coming on Aliyah to Eretz Yisrael.

The annual gathering of the Zionist underground in the Kovno Ghetto and their offspring, Kibbutz Kfar Massaryk, Succot 1956

The Partisan group at a gathering at Kibbutz Tel Yitzchak, Succot 1958

From the 1970s on, our meetings provided a somewhat of a natural framework and a warm home to integrate our comrades in arms who belonged to the ranks of the communists in the Ghetto.

Even subsequently for decades following the hasty Aliyah of the members of the Zionist camp of Soviet Kovno they did not join us. A few of them managed to join our ranks.

Continuing solidarity of the Partisan group during the annual gathering of 1964

Significant presence of the second generation at gatherings from 1965 and on

As time went by, these meetings were transformed into a sort of workshop for recording historic accounts on the subject of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust that still serve institutions of higher learning and academies throughout the Jewish world. This started during the course of our gatherings in the 1950s when Zvi A. Baron and I were requested to provide research papers on the resistance in Kovno Ghetto and the forests giving proper credit to the activities of the members of our group both individually and collectively. Naturally, we were helped a great deal by information that the veterans of Mildos 7 and others supplied in writing and orally through tape recordings. This painstaking work eventually produced a series of publications such as, "The Fortress Number Nine" in Sefer ha-Partizanim ha-Yehudim, Volume I, Merhavia, 1958, pp. 197-257; "The Fighter Organization of Kovno Ghetto" in Bi-Tefutzot ha-Golah, No. 30-31, Jerusalem, 1964, pp. 56-66; "To the Rudniki Forests" in They Fought Back, Tel Aviv, 1964, pp. 61-65; "Horror and Heroism" in From Beginning to End, Tel Aviv, 1985, pp. 261-311, and others. [All these documents were written in Hebrew and many have synopses in English.]

Our steadfast colleague Haim Galeen, has after a long period provided us with a vivid and detailed description on the activities and way of life at Mildos 7 and in the partisan forest in his book An Eye Looks to Zion, House of Fighters, 2001. It comes as no surprise that the enthusiastic reception held on the publication of this captivating book at the Igud Yotzei Lita (Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel) on 16 March 2001 turned into a reunion of the Mildos 7 veterans.

The second generation of the founders of Kibbutz Mildos 7, at a "Salute to their Parents"

Most recent reunion of the Mildos 7 veterans at the Iggud Yotzei Lita (Organization of Former Residents of Lithuania [in Israel])

They and their descendants were fortunate to renew again the over 40-year tradition of the regularly scheduled annual picnics that were held all over Israel — from 1949 in Rachel Levin's apartment in Tel Aviv to 1990 at Yosef Melamed's house in Caesarea. At this meeting, it was decided to take action against the wiping away from memory the crimes of the Lithuanians during the period of the Holocaust. This activity assumed international scope and remains a top agenda item of the organization.